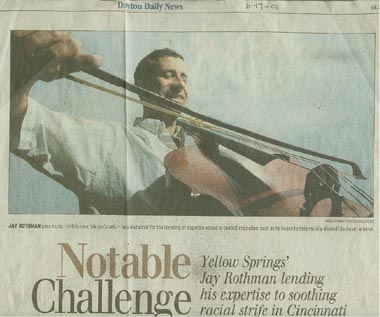

Dayton Daily NewsNotable ChallengeBy Laura Dempsey, June 17, 2001It would be tempting for Jay Rothman to see himself as a failure. Rothman has devoted his life to what may seem to be a futile task: conflict resolution. He goes where there's trouble - to Ireland, Israel, Sri Lanka and the Caucasus, to name a few - and uses his skills to bring people together, to pound out some way to make peace. |

|

|

| A look at

the world, however, makes it clear that old issues die hard, and conflict

resolution is one tough sell. But Cincinnati, for one, is buying. Rothman and his Yellow Springs-based consulting firm, the ARIA Group, has been given the prodigious task of guiding the racially divided city through a sea of attitudinal change in police-community relations, which reached a new low in early April when riots erupted after a white police officer shot and killed an unarmed, 19-year-old black man. It's not going to be easy. But Rothman, 43, is an optimist born of pessimism, who knows that a better future is within humanity's grasp. He calls himself a planter of seeds, whose goal is to give individuals, groups - whole communities, even - the tools to reach communal accord. And then he moves on, leaving it to those remaining to "carry the water, to actually deliver the goods." Besides, he said, "If we define conflict resolution as the end of conflict, I'd have to close up shop." Instead, he sees conflict as a big, ripe opportunity for growth, a chance to look hard and long at the whats, whys and hows of the ways we relate. There are reasons, he believes, for the world's struggles, reasons that go to the very core of each individual being. Nobody can change who they are. Rothman wants to help individuals see others the way others see themselves. His goal is to make each distinct voice heard, then weave the cacophony into a blend of complimentary sounds - notes that work together in compatible chords. An incredible dream, perhaps, but Rothman goes to work every day believing he will change the world, one voice at a time. The alternative is untenable. In other words, he says, voice trailing off, "If we can't do better...." Rothman became involved in Cincinnati's effort at racial healing by way of a lawsuit, filed in U.S. District Court by the Cincinnati Black United Front and the American Civil Liberties Union. The lawsuit charged the city of Cincinnati and the Fraternal Order of Police with racial profiling, a practice in which blacks are stopped or detained by police for no reason other than race. Even before filing the lawsuit, the plaintiffs' lawyers were looking for innovative ways to settle. Al Gerhardstein, Scott Greenwood and Ken Lawson, lawyers with long histories of civil-rights litigation, had been trying for decades to kindle lasting reform, only to be frustrated time and again as they watched court-ordered commitment spark and die. "I've been litigating in the police conduct area in Cincinnati since 1976," said Gerhardstein. "I've used the usual lawyer tools - I've sued people, used mediation - but it all seems so detached from the streets. And that's really what we're trying to do differently here. We can't solve this problem in a manner that keeps us detached from the people. We need to walk with them." And that's where Rothman came in. His name was given to Gerhardstein by the Andrus Family Foundation, a New York-based philanthropic organization interested in providing assistance and funding to efforts for racial reconciliation and improving police-community relations. Rothman had been heavily involved with Andrus in another of its projects: easing the transition for young adults moving from foster care to independence. "I was just chewing on this thing and called Andrus," said Gerhardstein. "I said I wanted to do this thing in Cincinnati - did they have any ideas? They proposed Jay Rothman and his ARIA Group," based, coincidentally and conveniently, up the road in Yellow Springs."I was expecting somebody from Colombia or something," he said, laughing. Andrus also pledged $100,000 in a challenge grant to the city of Cincinnati, which came through with $100,000 of its own after some great City Council debate. U.S. District Court Judge Susan Dlott approved Rothman's plan, so he and his staff have hit the ground running, developing and implementing a detailed plan that pulls in the voices of the people - anyone with a vested interest is called a "stakeholder" in ARIA parlance - through questionnaires and interviews. That data will be the basis for a yearlong process of setting goals through the use of feedback groups and the input of experts. All parties to the lawsuit will be key players in the process; all data except that which would identify individuals will be public information."That's the whole key to this," agreed Gerhardstein. "Communities' social problems have been resolved behind closed doors. In 1998, the Justice Department meditated an agreement - a bunch of stuff that just never got done. It may be harder at the end to settle the case because you can't hide the ball." "The stakeholders are going to be looking for their thoughts, their views, their words to be represented," Rothman said. "It will really hold our feet to the fire."The findings will be presented to the parties to the lawsuit, and Rothman hopes the spirit of collaboration will carry over and see them through to a settlement before any adversarial instinct recurs. It will be up to Judge Dlott to approve any settlement, but Rothman says that nobody's waiting: His plan is to develop projects, for example, that neighborhoods can adopt immediately. Rothman's staff has grown from seven to 33; he's expanded operations from his large, airy Yellow springs home/office base to a Cincinnati satellite housed in donated space. The initial $200,000 budget has doubled, and Rothman has vowed to raise the additional funding himself. People have been unbelievably willing to help, he said, donating time and expertise, supporting the effort any way they can. "There's a tremendous effort in Cincinnati," he said. "People are stepping up to the plate, asking how they can do better, wanting to find out what brought us here. I'm seeing the best. It's wonderful," he said.Rothman remains adamant that conflict based on identity can be eased, even resolved, with the right tools and, more important, the right frame of mind. "Whether racial profiling happens or not is less important than the underlying, deeper tension, fear, mistrust, the legacy of separation that we haven't solved with affirmative action, with integration." "Racial profiling is a symptom of a cause," Rothman said. "We could collect statistics on police stops - that would be OK - but it won't solve the problem. The police are put on the front line of addressing social ills, problems that have to do with racial identity, economics and history…We have to address that head-on. It's so much more complex than statistics. "Rothman's credentials include a degree from Antioch (1980); a master of arts (1985) and doctorate in international relations from the University of Maryland (1987). He embarked on conflict resolution as a career at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he led workshops that included Israelis and Palestinians. A growing reputation and undying need for his expertise took him around the world, where he was hired to mediate, teach and train diplomats, students, activists and business executives in what he calls the art and science of conflict resolution. He's run conflict-resolution programs in areas where the problems are overwhelming, sitting with loyalists and nationalists in Northern Ireland, between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, and with about 15 different ethnic groups in the Caucasus region of the former Soviet Union, and he's mediated conflict resolution with everyday workers in U.S. businesses. Cincinnati, he said, should be proud of its courage in facing an entrenched, often ignored problem. "The best way to predict the future is to create it," he said. For his part, the "seed planter" plans to keep an eye on the city to enjoy the fruits of his effort."We're often brought in to be heroes," he said, "but when all is said and done, they are on their own. Really, it's better when they forget about us. If we do our job right, Cincinnatians will say they did it themselves." top Back next |

||