CHAPTER 5

POLITICAL LEARNING AND

POLITICAL COMMUNICATION

|

Learning Objectives: · What are the

major influences in forming the political values of children? · How have the

sources of political learning changed over time? · What special

methods did the German Democratic Republic use to socialize political values;

how successful were these methods? · What are the

major sources of political information today? |

Go to Family Influences

Go to The Educational System

Go to State Actions

Go to Informal Sources of Learning

Go to Mass Media

Go to Suggested Readings

How

do we form our political identities? If stable political systems require that

the citizens hold values consistent with the political process, then one of the

basic functions of a political system is to perpetuate the attitudes linked to

this system. This process of developing the political attitudes and values is

known as political

socialization. (1)

Political

socialization is a life-long process. Learning begins at an early age, long

before people are old enough to participate formally in the political process.

Most children acquire a sense of class, religious, and national identity before

their teens. Early youth is also a time when basic political orientations

develop, when the beliefs anchoring the political culture take root, and when

partisan and ideological tendencies first emerge. This process continues into

adulthood as people develop policy beliefs that reflect their

previously-learned values. New experiences are often viewed through the prism

of previous values. Some elements of the socialization process, such as the

media, also perform a crucial function of communicating between citizens and

political leaders.

The socialization process is especially

significant for Germany. The change in regimes in 1945 and again in 1989 have

twice created the need to reform political values to support the new system.

This chapter examines these experiences, and how contemporary political values

are formed. During the 1950s, the West German government used the schools and

the mass media in a large-scale reeducation campaign to transform the culture

inherited from the Third Reich. As democratic values took root in the West, the

nature of socialization shifted to reinforcing these beliefs and providing the

information that people need to make informed political decisions. The

socialization role of parents changed as they became more supportive of

democratic values. The contemporary media also provide a rich source of

information about politics and a vehicle for political communication.

Western reeducation activities pale, however,

in comparison to the socialization efforts in the East. The GDR government

tried to create a new social and political environment that enveloped the

individual. The government used a variety of "transmission belts,"

such as schools, mass organizations, and the SED itself to educate the public

politically and to reshape social relations. The state was an omni-present force in the East, or so it must have seemed to many of its citizens. Political indoctrination activities

never abated in the East. Perhaps this was an indication of the government's

inability to remake the political culture despite its more extensive

reeducation efforts (see chapter 4). In any case, the collapse of the East and

the integration of its citizens into the Federal Republic renews

the importance of political socialization as an agent of political change.

Political learning in most societies begins

within the family. Parents are usually the major influence in forming the basic

values and attitudes of their children. During their early years children have

few, if any, sources of learning comparable to their parents. Family

discussions can furnish a rich source of political information as parents

provide political role-models for their children. Thus, children often

internalize their parents' attitudes and beliefs. Most parents and children

also share the same cultural, social, and class milieu, providing additional

sources of indirect political cues. For all these reasons, the family normally

has a pervasive effect on the future adult's thoughts and actions.

In post-WWII Germany, the role of the family

was more ambiguous. Researchers linked the traditional authoritarian style of

German family patterns to authoritarian aspects of the political culture. As

Ralf Dahrendorf, for instance, maintained that the

German father furnished a model for the Kaiser or the Führer (or the SED-led

state in the East): (2)

the German father is, or at least used to be, a

combination of judge and state attorney: presiding over his family,

relentlessly prosecuting every sign of deviance, and settling all disputes by

his supreme authority.

This characterization was more

true of the family earlier in the twentieth century, but this pattern of

family relations partially carried over to the postwar period. Gabriel Almond

and Sidney Verba, for example, found that West

Germans were less likely than either Americans or Britons to say that they

participated in family decision making during their youth. Furthermore, these

nondemocratic family environments affected adult feelings about the democratic

process.(3)

As in many new political systems, the family

often played a limited socialization role in postwar political education. Many

adults did not openly discuss politics because of the depoliticized environment

of the period. In addition, parents were understandably hesitant to discuss

politics with their children for fear of discussing the past. "What did

you do during the Third Reich, father?" was not a pleasant source of

conversation for the parents or their offspring. Furthermore, even if western

parents had wanted to educate their children into the democratic norms of the

Federal Republic, they were ill-prepared to do so because their own democratic

experiences were limited. Most parents in the 1950s had spent the majority of

their adult lives under authoritarian regimes. These experiences served as

examples of what politics should not be, rather than fostering democratic

political values. In other words, adults were learning the new political norms

at almost the same time as their children.

Starting from these uncertain beginnings, the

content and importance of parental socialization in the FRG changed over time.

As people accepted democratic principles and values, the frequency of political

discussion increased. Family conversations about politics are now commonplace.

Moreover, today’s parents were themselves raised under the political system of

the Federal Republic. Helmut Kohl once described them as "the generation

blessed by the grace of late birth." These parents thus can pass on

democratic attitudes that they have held for a lifetime. (4)

Social relations in the family have also

changed. The dominating-father role has largely yielded to a more flexible

authority relationship within the household, especially in middle class

families. Western parents now place more emphasis on teaching their children to

be independent and self-sufficient, rather than obedient. For instance, a 1999

survey comparing East and West found that barely half (56 percent) of

Westerners over 65 thought parents should stress independence in raising their

children, but this increases to 83 percent among 25-34 year olds who are the

parents of today.(5) Younger Germans are now less likely to

be deferential to authority, and more independent–and democratic–in their

political values.

Socialization

patterns in the East followed a different pattern, however. In the postwar

period, families in the East had inherited the same structured family

relationships and hierarchical authority patterns as in the West. Eastern

parents also had lived through the rise and fall of the Third Reich and then

the creation of a new political order. Parents initially were hesitant to talk

about politics, and in any case were themselves learning the new communist

norms of the German Democratic Republic.

Over time the family's role as a socializing

agent also grew in the East. (6) Although the state

bombarded young people with political indoctrination, the family was an

important source of political learning. For example, a 1990 survey of

adolescents in both Germanies found that 62 percent

of Eastern youth frequently discussed politics with their parents, compared to

only 32 percent in the West. (7) Most young people also

claimed to hold the same political opinions as their parents. The personal

closeness of family ties was one reason why parents were an important source of

political cues. In addition, the family was one of the few settings where

people could openly discuss their feelings and beliefs. The family setting

created a private sphere where individuals could be free of the watchful eyes

and ears of the state. Here the state could be praised, but doubts could also

be expressed.

The collapse of the GDR forced many adults to

rethink their political beliefs and past practices. Parents are again learning

the norms and procedures of a new political system at the same time as their

children. For instance, the same 1999 World Values Survey found that Easterners

were more likely than Westerners to express respect for parents and authority

in general. In addition, younger Easterners are less likely than Westerners to

say that parents should stress independence in raising their child, and more

likely to emphasize obedience.(8) These values are changing

among those raised since the fall of the Berlin Wall, but it will take time

because social values in the East fully adopt to the

new social structure.

Because of these changes over time, the ‘generation

gap’ in many political values is greater in Germany than in many other

established Western democracies. Youth in the West are more liberal than their

parents, more positive about their role in the political process, more postmaterialist, and more likely to engage in

unconventional forms political action. (9) Eastern youth are

also a product of their times. The youthful faces of the first refugees exiting

through Hungary in 1989 or at the democracy protests in Leipzig or East Berlin

demonstrated the importance of the youth culture within East Germany. And most

research indicates that Eastern young are more quickly accepting the new social

and political order of the Federal Republic. Like the family in the film Goodbye

Lenin, the older generation has experienced a mid-life change, while the

young are being raised in this new social order.

The

educational system is another important source of political learning. In

contrast to the family, governments can control the content of education and

use it to develop political values–this is typically done when a country

experiences a change in regime. Thus, political leaders in both West and East

saw the educational system as an important tool for developing new political

beliefs, albeit with different goals in mind. The Western Allies and

politicians in the Federal Republic wanted to enlist the schools in their

efforts to reeducate the public to support for the democratic norms of the new

state.(10) The Soviets and East German politicians wanted

to create a "socialist personality" consistent with their new social

and political order.

In the West, the regime expanded the

curriculum to include new courses in civics and more offerings in history.

Instruction aimed at developing a formal commitment to the institutions and

procedures of the Federal Republic. History courses worked to counteract the

nationalistic views promulgated under Weimar and the Third Reich. Social

studies classes stressed the benefits of the democratic system, drawing sharp

contrast to the Communist model. In addition, modern teaching methods

supplanted the authoritarian educational structures and classroom practices of

the past. More participatory forms of education, and even student

‘co-administration” programs, signaled a new set of social norms. These

innovations marked a sharp change from the traditional authoritarian ways of

the German educational system.

YouTube video on

German education system (2:44 min)

Beginning in the mid-1960s, textbooks began

emphasizing an understanding of the dynamics of the democratic system: interest

representation, conflict resolution, minority rights, and the methods of

citizen influence. The model of the passive citizen yielded to a more activist

orientation. Education adopted a more critical perspective on society and

politics. The new texts substituted a more pragmatic view of the strengths and

weaknesses of democracy for the idealistic textbook images of the 1950s. The

system sought to prepare students for their adult roles as political

participants.

The

political impact of formal schooling is typically greatest when prior family

learning is lacking, such as the conditions in postwar West Germany. The

reeducation program helped to develop a stronger sense of political interest

and democratic beliefs among West German youth. In the early 1970s, for

example, West German students ranked highest in support for democratic values

in a 10-nation study of youth.(11) Nevertheless, the

broader social and political trends in society gradually made this program of

formalized political education redundant. Social studies courses now reinforce

democratic political beliefs learned from parents and peers, rather than

creating them in the first place. Thus, the education system in the West now

plays a socialization role that is similar to civics courses in the United

States, Britain, and other established democracies.

The

school system also played a key role in the GDR's program of political

reeducation, although the ultimate political goals and therefore the content of

instruction were much different.(12) The schools attempted

to create a socialist personality that encompassed a devotion to communist

principles, a love of the GDR, a feeling of socialist brotherhood with the

Soviet Union, and participation in the activities of the state. The ideological

content of instruction was more extensive than in the West, and did not

moderate over time. The regime’s principles reached into the curriculum in many

ways. Civics courses stressed Marxist-Leninist principles. Economics courses

stressed the inevitable decline of capitalism and the eventual victory of

socialism. History classes explained the Third Reich as the consequence of

capitalist imperialism and portrayed the Federal Republic as the Nazi’s

successor. The schools stressed the importance of the collective over the

individual. The GDR's constitution stated the government's goal to create:

"a socialist community of well-rounded and harmoniously developed persons

who are inspired with the spirit of socialist patriotism and

internationalism."

Yet the rhetoric of education regularly

conflicted with reality. Paramilitary training was a regular component of the

curriculum and became mandatory for 9th and 10th graders in 1978, but social

science and history texts proclaimed the government's peaceful goals. Educators

forecast the inevitable victory of world socialism, as the gap between Eastern

and Western living standards steadily grew. Given these contradictions, these

education efforts may have had limited effect in reshaping the beliefs of the

young. In part, the educational system was trying to develop values that were

inconsistent with the realities of politics. Many young people certainly

accepted the rhetoric of the regime, but surveys indicate youth's growing

political disaffection during the 1980s.(13)

German unification produced fundamental

changes in the Eastern educational system. (14) Western

experts oversaw a wholesale restructuring of curriculums, and again the

educational system was used to reshape citizen values. Just as foreign language

courses in Russian were replaced with English as a second language, education

in socialist economics gave way to principles of market economies. It was

relatively easy to replace old textbooks with new editions from the West. The

FRG government also replaced thousands of school administrators and university

instructors with new personnel. Gradually, the content of the educational

systems in the East have converged with those of the West.

The Structure of Education

The

educational system is also important in shaping the social structure. Public

education in Germany historically functioned with two contrasting goals. One

goal emphasized personal growth and the development of intellectual creativity

(Bildung) among the top students who

comprise the future leaders of society. Another goal stressed job-oriented

education (Ausbildung) for the masses.

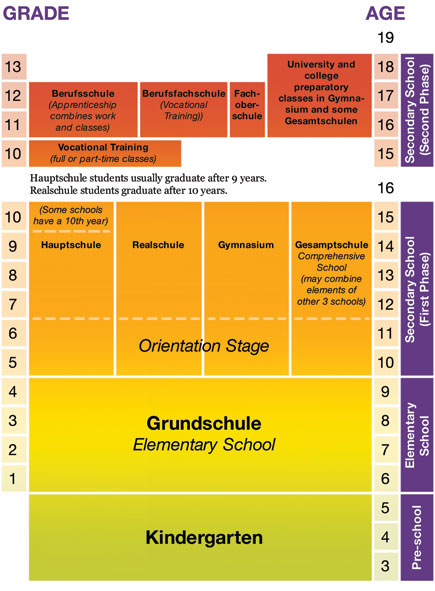

The Federal Republic’s adherence to these two

differing educational models leads to a highly structured and stratified

educational system. Figure 5.1 shows the general structure of the educational

system, although this varies across states because educational policy is a

state responsibility. The social stratification of the educational system most

clear appears at the secondary school level. All students attend a primary

school together for their first four years, and then are divided into one of

three distinct secondary schools tracks. Students in each track attend separate

schools with different facilities, teachers, and curriculums. One track, the

main school or Hauptschule, provides a

general education leading to a working class occupation. This limited formal

schooling ends at age 15 in most Länder, and students then begin a program of vocational training.

About two-fifths of students follow this track.

Figure 5.1. The Structure of Education

The second track is the intermediate school, or Realschule. About a quarter of secondary students

now attend a Realschule. The Realschule

mixes vocational and academic training. For example, students study a second

foreign language and take higher level mathematics. Students graduate from the Realschule at age 16 and receive a completion certificate (Mittlere Reife).

Graduates choose between an apprenticeship or a more

extended period of technical training, perhaps even including study at a

technical college. Most Realschule graduates hold

lower middle-class occupations or work in the skilled trades.

The second track is the intermediate school, or Realschule. About a quarter of secondary students

now attend a Realschule. The Realschule

mixes vocational and academic training. For example, students study a second

foreign language and take higher level mathematics. Students graduate from the Realschule at age 16 and receive a completion certificate (Mittlere Reife).

Graduates choose between an apprenticeship or a more

extended period of technical training, perhaps even including study at a

technical college. Most Realschule graduates hold

lower middle-class occupations or work in the skilled trades.

Academic training at a Gymnasium,

an academic high school, is the third track. The Gymnasium is the traditional

route to social and economic success. About 25 percent of secondary school

students in the FRG attend a Gymnasium, a substantial increase from a

generation ago. The curriculum stresses advanced academic topics as preparation

for a university education. After completion of final year exams, the Gymnasium

student receives an Abitur, which confers a

legal right to attend a university.

Nearly all German universities are government

institutions. Once at the university, students follow the traditional Humboltian model of academic learning. For the student this

means the freedom to develop one's intellectual potential largely unfettered by

regulations and formal course requirements. In many social science fields,

students are free to develop their own program of studies. The courses

themselves are often equally unstructured: no quizzes, no finals, no homework,

no required attendance, and no grades. Science programs are usually more

structured, but still relatively open by American standards. The university

system was designed for a small number of strongly self-motivated students,

allowing great freedom to the individual.

This highly stratified system of public

education in the Federal Republic has prompted criticism on several fronts.(15) One persisting criticism highlights the unequal public

spending on the different tracks. Educational spending is concentrated on the

academic track rather than the vocational tracks. The Gymnasiums have lower

student/teacher ratios than the Hauptschulen and Realschulen; and teacher qualifications for the Gymnasium

are more rigorous than for the other tracks. In short, there is an obvious

distinction between education for the masses and education for elites.

The educational system did not create social

inequality within West Germany, but the system tends to perpetuate this

inequality. After only four to six years of primary schooling, students are

directed into one of the three tracks. At this early age, family influences are

still a major factor in the child's development. Most children assigned to the

academic track are from middle-class families, and most students in the

vocational track are from working class families. For instance, if the value

100 represents the average student's chance of attending a Gymnasium, then the

chances for different social classes in 1980 were:

|

Civil

servant’s |

Self-employed’s |

Salaried

employee’s |

Manual

worker’s |

|

396 |

212 |

140 |

21 |

Thus, the child of a government official has

nearly 20 times the chance of attending a Gymnasium as the child of a manual

worker. These social differences are replicated in university enrollments, and

have not greatly lessened over the years. Furthermore, because of the social

and educational gap between secondary school tracks, few students take

advantage of the option to transfer to a higher-level school. The educational

system thus inevitably reinforces class distinctions within society.

Reformers have repeatedly attempted to lessen

the elitist bias of the FRG's educational system. One reform was the creation

of comprehensive schools that include all secondary school students in a single

school with differing curricula. Without a uniform national policy, only half

the state now have comprehensive schools as an

optional fourth track. About a tenth of secondary school students are now

enrolled in comprehensive schools.

Reformers were more successful in other

areas. Several state governments agreed on curriculum reform that narrows the

gap between secondary schools. In these reforms the Hauptschule

curriculum has shifted from the basic, practically oriented, and atheoretical subject matter toward a more specialized set

of course offerings. The curriculum and resources of the Realschule

underwent similar upgrading, contributing to its growing popularity and enrollments.

Another significant reform expanded access to

the universities. In the early 1950s only 6 percent of college-aged youth

attended a university. Today, more than 30 pursue university studies. The

increase partially results from the growth of Gymnasium graduates with the

necessary Abitur to enter the university.

University programs broadened to include new fields of study. Educators also

made a concerted effort to provide alternative educational paths into the

universities for those who did not attend a Gymnasium (although few students

use these alternative paths). The Federal Republic’s university system retains

an elitist emphasis, but its upper class accent is a little less distinct.

Of course, the socialist ideology of the GDR

led to a much different educational structure in the East. By the 1960s,

comprehensive 10-year polytechnical schools were the

core of the educational system.(16) Students from different

social backgrounds, and with different academic abilities, attended the same

school -- much like the public education system in the United States. Those

with special academic abilities could apply for the extended secondary school (Erweiterte Oberschule

[EOS]) during their twelfth year, if they supported socialist political values.

Less than a tenth of the young followed the academic track to university

training.

The contrasting educational structures of the

FRG and GDR illustrate the practical problems posed by German unity. The

unification treaty called for the gradual extension of the Western educational

structure to the East, although several Eastern Länder

have emphasized comprehensive schools at the secondary level. Ironically, the

restructuring of Eastern schools lead to new pressures for liberal reform

within the Federal Republic's educational system.

Although both the FRG and GDR actively tried

to shape the political values of their citizens, the role of each state was

sharply different. With the exception of the school system, the reeducation

efforts in the West largely occurred through indirect mechanisms, relying on an

autonomous media, social groups, and the powers of persuasion. Explicit

political education by the government decreased as the new system took root.

The East German government, in contrast, took a very active and direct role in

the socialization process that even went beyond the factors we have already

discussed. And in contrast to the West, this role remained constant or even

increased over time.

YouTube video on GDR

propaganda film (4:07 min)

A cornerstone of the East German

socialization process was a system of government supervised youth groups. Most children

in primary school were enrolled in a young Pioneer group. The Pioneers combined

the normal social activities that one might find in the Boy Scouts or Girl

Scouts with a basic dose of political education. At age 14, about three-fourths

of the young graduated into membership in the Free German Youth (FDJ) group.(17)The organization stressed

political themes, and participation in a FDJ collective provided the state with

another opportunity to direct the political development of the young and foster

a socialist personality. The FDJ was also a training

and recruiting ground for the future leadership of East Germany, selecting the

brightest and most politically aware for higher positions in the organization

and future membership in the SED.

Another important socialization activities was the Ordination of Youth (Jugendweihe).

This ceremony had developed in Germany as a secular alternative to the

Christian confirmation. The GDR used this ceremony to strengthen the socialist

identity of the young. Each spring, 14-year-olds assembled in public ceremonies

to pledge their commitment to socialist beliefs, brotherhood with the Soviet

Union, and the principles of international socialism. Table 5.1 presents the

four pledges that were the heart of the ceremony, illustrating how political

indoctrination was intermixed with the rites of passage to adulthood. While

West German youth celebrated their coming of age at a birthday party or similar

occasion, East Germans celebrated by pledging their

fraternal loyalties to the Soviet Union. Surprisingly, after the fall of the

GDR this tradition has continued in the East, but now without the heavy

political overtones.

|

Table 5.1

The Four Pledges of the East German Youth Ordination · As young

citizens of our German Democratic Republic, are you prepared to work and fit

loyally for the great and honorable goals of socialism, and to honor the

revolutionary inheritance of the people? · As sons and

daughters of the worker-and-peasant state, are you prepared to pursue higher

education, to cultivate your mind, to become a master of your trade, to learn

permanently, and to use your knowledge to pursue our great humanist ideals? · As honorable

members of the socialist community, are you ready to cooperate as comrades,

to respect and support each other, and to always merge the pursuit of your

personal happiness with the happiness of all the people? · As true

patriots, are you ready to deepen the friendship with the Soviet Union, to

strengthen our brotherhood with socialist countries, to struggle in the

spirit of proletarian internationalism, to protect peace and to defend

socialism against every imperialist aggression?

|

Other social spheres mirrored the

socialization activities of the youth groups. At work, individuals participated

in labor collectives, where employment and politics issues were discussed.

Nearly a third of the population belonged to the state-sponsored Society for

German-Soviet Friendship (DSF), and almost a fifth of all women belonged to the

Democratic Women's Federation of Germany (DFD). Such mass organizations

provided the government with other transmission belts to educate the public,

and control social and political norms. Government officials also monitored the

content of mass media, literary magazines, book publishers, and performing artists.

Publications with political themes were subject to especially close scrutiny.

The censorship even went as far as excluding Hansel and Gretel from some

publications of Grimms' Fairy Tales; socialist states

did not recognize the existence of hunger and did not condone disrespect toward

one's elders. The government-approved writers union further regulated those who

would tell a story, write a play, or pen a novel.

The politicization of social life even

extended to sports. The GDR encouraged sports as a way to keep people socially

involved while promoting the value of physical fitness that drew upon the

traditions of the socialist working class movement. In addition, the famous

East German Olympic sports machine provided a source of national pride and became

a basic tool of GDR foreign policy. The government used the medal count at the

summer Olympics as an indicator of the domestic accomplishments and new

international stature of the GDR.

Finally, when persuasion failed the

government relied on its powers of physical control and intimidation. The

infamous Ministry for State Security (Stasi) was in charge of domestic

security. Stasi agents not only collected data on radicals who might pose a

threat to the state, they also were a tool for enforcing compliance with the

regime. The Stasi had its agents in social, economic and political

organizations in order to monitor and control their actions. The Stasi

maintained files on more than 6 million individuals, nearly a third of the

entire population. Several hundred thousand part-time informants provided

information on co-workers or neighbors who engaged in "anti"

behaviors. The expression of political criticism might threaten one's job

security or the ability of one's children to attend university -- or might result

in prosecution by the state. In the wake of German unification, thousands of

Easterners recounted stories of neighbors who were arrested an imprisoned by

the Stasi, children who were unable to attend a university because of their

questionable political record or the records of their parents, and political

dissidents who disappeared into Stasi-run prisons. If East Germans had

internalized the norms of the regime, would such a security apparatus have been

necessary?

|

The Lives

of Others The 2007 movie, The Lives of Others,

tells the story of how the Stasi monitored a group of artists and writers in

the years leading up to the collapse of the GDR. It illustrates the Stasi’s

power under the GDR, and how individuals accommodated themselves to the

state’s power–and how a captain in the Stasi struggled with his role in this

process. Two thumbs up from Ebert and Roeper. It

won the best foreign language film award at the 2007 Oscars. |

These examples show the reality of life in

the GDR. The SED and state institutions directed most aspects of social,

economic, and political life. From a school's selection of texts for first

grade readers to the speeches at a sports awards banquet, the values of the

regime touched everyday life. For those who accepted these values, the

political socialization but the state was unnoticed because it was merely an expression

of values they shared. Despite these extensive efforts, however, the remaking

of the East German culture remained incomplete. This was partially because of

the contradictions between the rhetoric and reality of the regime, and because

Easterners were aware of a different way of life in the West.

Informal

Sources of Political Learning

In any nation, informal personal relations

constitute another important source of political learning. As soon as children

begin to explore the world outside their parents' home, they develop

friendships and peer-group ties that teach them about social (and implicitly

political) relations. Co-workers in the factory are often a valuable source of

information about political matters. Friends discuss politics, compare ideas,

and debate current political issues. Although difficult to measure in a

systematic fashion, these informal contacts constitute a crucial part of the

socialization process.

The 1999 World Values Survey asked about

involvement in such informal networks. The survey found that 59 percent of

Germans said they spend time with their friends on a weekly or more frequent

basis, 28 percent spent time with others in social clubs, 12 percent with

friends from work, and 11 percent with friends from their church. And as might

be expected, the frequency of these social connections was higher among the

young. For example, while only 33 percent of 45-54 year olds spent time with

friends on a weekly basis, 86 percent of those 15-24 spent time with their

friends.

Such peer groups can easily influence the

values of their members. There is much interaction and exposure occurs in the

group, which persists even when the influence of family and schools begins to

wane. Receptivity to the norms of the group is also high, because it is

composed of individuals with strong personal ties and common interests.

Explicit political learning is a minor part

of most youth groups, but under some circumstances the peer group may exert a

substantial impact on political beliefs. For instance, a variety of

biographical studies and impressionistic evidence suggests that the student

movement of the 1960s created a youth subculture in the FRG that socialized a

new political perspective among many university students.(18)

The friendship groups and subculture formed during this period have endured

into adulthood for many activists of the 1960s. In the East, most interaction

with one's peers involved a greater degree of political learning because this

interaction was often structured by membership in the FDJ, youth brigades, or

other officially-sponsored youth associations. Even in the GDR, however, peer

networks revolving around environmental discussion circles or church groups

seemed to nurture those who harbored doubts about the system.

Personal discussions with friends, family,

and political activists can be a meaningful source of political learning. Most

adult friendship networks reinforce previously-formed beliefs, rather than

providing a source for learning new political values. By adulthood most

individuals have developed their basic political values and thus any new

learning must first overcome previous learning. In addition, people generally

select friends with similar social and political values. Nevertheless, the interaction

among friends and co-workers signifies an important source of political

information and an opportunity to discuss political viewpoints. A steelworker

in the Ruhr, for example, hears about politics from his co-workers and other

working-class neighbors and friends. This social milieu provides repeated cues

on which issues are most important to people like oneself, which policies will

provide the most benefit, and which party represents these interests.

Similarly, a Bavarian Catholic learns about political issues at weekly church

services, from Catholic social groups, and from his or her predominately

conservative Catholic friends.

Finally, personal interactions can provide

information that is qualitatively different from newspapers, television, and

other mass media. Face-to-face communication is interactive. People can discuss

information until its meaning is understood; the transfer of information can be

tailored to the recipient. Friendship ties often make personal communication a

more persuasive source of information than impersonal newspaper accounts of the

same events.

Throughout their adult lives, people need

information about current events and new political issues in order to perform

their responsibilities as citizens. The mass media are prime sources of such

information. People often lack direct experience with government and specific

policy outcomes. In many instances, the media provide the only linkage between

citizens and political affairs. Still, the media’s role as a socialization

agent is normally limited. The media less likely than the family, peers, or

school to socialize new political beliefs. Rather, the mass media provide

information that reinforces prior opinions or provides information for

evaluating new events in the context of these opinions.

Germans place a heavy reliance on the media

as a source of political information. Even early studies of the West German

public found that media usage was exceptionally high among the public, a trait

that persists to the present.(19) Similarly, East Germans

had a voracious appetite for the printed word. This section examines how the

contemporary media provide political information to the citizenry.

The Press(20)

Throughout modern German history, the press

has been closely involved in the political process. During the Weimar Republic,

various social and political groups developing their own network of newspapers;

about one quarter of all papers had official or unofficial ties to a political

party. The exploitation of the press reached its worst level under the National

Socialists. The Völkischer Beobachter was the official organ of the National

Socialist movement, substituting nationalism, racism, and anti-liberal

propaganda for factual news. The regime suppressed non-Nazi publications and

eventually forced most to close.

Those charged with overseeing the

redevelopment of the press in the Federal Republic kept this historical legacy

in mind. Immediately after the war, the Allied military forces licensed

newspaper publishers within their respective occupation zones. Only newspapers

and journalists who were free of Nazis ties could obtain a license. The Allies

also tried to encourage political diversity in the media. The Basic Law

(Article 5) ensured that the press would be independent and free of censorship,

and licensing restrictions were removed in late 1949. By then, the overall

structure of the postwar press was established.

This pattern of press development had two

consequences. First, journalists, publishers and the government created a new

journalistic tradition, committed to democracy, objectivity, and political

neutrality. During the early postwar years, the press had an important part in

the political education of the public. Along with radio, newspapers shaped

public images of the new political system and developed an understanding of the

democratic political process. Today, the press is not only responsible for the

dissemination of information, but monitors the actions of government and

educates public opinion. The public and political leaders expect newspapers to

be social and political critics--even if criticism is often unwelcomed. Press

laws grant the media specific legal rights to assist them in this task: the

right of access to government information, the legal confidentiality of

sources, restrictions on libel suits, and limits on government regulation. At

the same time, most newspapers avoid the political propagandizing of the past

by adopting political neutrality and clearly separating factual news from

editorial evaluation.

Second, the postwar pattern of press

development produced a regionalization of newspapers. The licensing of

newspapers within each occupation zone created a network of local and regional

daily papers that continues today. Each region or large city has one or more

newspapers that circulate primarily within that locale. In 2010, there were

over 350 daily newspapers in the Federal Republic, with a combined weekday

circulation of about 25 million. Following unification, the newspapers in the

East were generally integrated into this same framework. Most of the prominent

GDR newspapers were sold to Western buyers, and only a few pursued their own

independence. This produced new regional media centers in Berlin, Leipzig and

other eastern cities. However, newspaper readership and circulation has been

declining over the past two decades, as people find other sources for their

daily news.

The decentralization of the press produces

diversity and pluralism in political commentary, but it also means that the

Federal Republic lacks the common national media environment found in Britain,

France and other European states. In both content and circulation patterns, the

regional press might bear a closer resemblance to American newspapers than to

its German antecedents.

The average citizen has several newspapers

from which to choose. Table 5.2 lists the newspapers with the largest

circulation in 2010. Bild Zeitung has the largest circulation with almost 3

million daily readers. The Bild is the only

truly national paper in the Federal Republic, sold at almost every kiosk and

newspaper stand. However, the Bild and the

other boulevard newspapers offer outlandish stories focusing on criminal

activity, bizarre events, or celebrity lifestyles. A daily diet of such

information can hardly develop a well-informed and sophisticated public.

|

Table 5.2 The Top Ten Daily Newspapers by Circulation in

2010 |

|

|

|

Newspaper group |

Circulation (in ‘000s) |

|

|

Bild-Zeitung |

2,900 |

|

|

Westdeutscher Allgemeine Zeitung |

807 |

|

|

Cologne Group |

515 |

|

|

Süddeutsche Zeitung |

428 |

|

|

Frankfurter Allgemeine |

363 |

|

|

Rheinesche Post |

354 |

|

|

Augsburger Allgemeine |

330 |

|

|

Zeitung Thüringen

|

306 |

|

|

Freie Presse |

283 |

|

|

Nuernberger Nachrichten |

280 |

|

|

Source: World Association of Newspapers, World Press

Trends 2012. |

||

Several "quality" daily newspapers

-- Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung,

Die Welt, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and the Frankfurter Rundschau--

have national reputations because of their sophisticated and detailed news

coverage. Their quality is comparable to the New York Times, Los

Angeles Times, or the Washington Post. These papers are widely

read by political and business elites, and they are available by subscription

or from newsstands throughout the country. Because of their elitist orientation

the circulation figures for the quality press are quite modest.

List of German Newspapers

available online

Several weekly newspapers and news magazines

are also part of the elite press. Die Zeit and

the Welt am Sonntag are national papers that

review the news of the past week and provide an analysis of recent events.

Probably the most influential single publication in the Federal Republic is the

weekly news magazine, Der Spiegel. Its weekly issues combine coverage

of on-going news events with investigative journalism.

Most people read neither the best nor the

worst of the press, but draw their information from their local or regional

newspaper. A citizen of Hamburg reads the Hamburger Abendblatt,

the Volksstimme Magdeburg is

popular in Saxony-Anhalt, a Cologne resident subscribes to the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger,

Leipzig residents read the Leipziger Volkszeitung, and so forth. In smaller towns the

citizens might subscribe to a small local paper, which devotes more attention

on local news and public interest stories.

Germans

place a high premium on being informed about political matters, and most

citizens rely on newspapers and other printed media as a source of information

on current events. For example, a survey conducted during the 2013 election

found that newspapers were cited as the second most important source of

political information (by 17 percent) and the majority reported regularly

reading a newspaper for information.(21)

The press performs a distinct function in the

process of political learning in Germany (and other established democracies).

Rather than influencing basic value formation, newspapers are a source of

contemporary political information. The media are probably more influential in

determining what people think about, through their choice of news stories, than

in actually influencing what people think. Still, newspaper readership is

related to certain aspects of a participatory political culture. Studies

regularly find that regular newspaper readers are more involved in politics and

more informed about political matters.(22) Reading a

newspaper might not create these orientations, but access to a ready supply of

political information is necessary to sustain this behavior.

Questions often arise over the political

orientation of the press. On the one hand, liberals note that most major

newspapers openly profess impartiality and include such terms as überparteilich or unabhängig

("nonpartisan" or "independent") under the title banner.

Yet, their editorials generally reflect conservative viewpoints. The Frankfurter

Rundschau, Der Spiegel and TAZ

are notable liberal exceptions among a generally conservative press. On the

other hand, conservatives point to evidence that most newspaper journalists

lean toward the SPD. Periodic political criticism of press coverage is probably

an inevitable feature of a free press, and Germany is not exceptional in this

regard. Nevertheless, most of the major national newspapers are known for their

attempt to separate editorial judgement and news

reporting, giving the public access to a diverse and high quality press.

Radio and Television

Germany entered the age of the electronic

media -- radio and television -- during the Weimar Republic. The radio became a

regular part of everyday life in the 1920s and early 1930s. Quickly the radio

became an important source of news and entertainment for the average citizen.

The world's first regular television service began in Berlin in 1935;

television usage grew very slowly, however.

The development of the electronic media

differed in important ways from that of the printed press. Newspapers were

privately owned; radio and television were considered public services. The

Weimar government owned a majority of the shares in the public broadcasting

stations, and a government ministry regulated what went out over the airwaves.

The Third Reich fully exploited the power of this new medium. Hitler

communicated directly with the population via the radio, which magnified his

considerable oratorical skills. The Third Reich's propaganda ministry relied on

radio broadcasts to generate public support for the regime and develop a

national consciousness. The Nazis considered radio's influence so powerful that

receivers built during the war were constructed to receive only German

stations. Listening to foreign radio broadcasts could warrant the death

penalty.

In the Federal Republic, the Western Allies

reestablished a regional radio service within each occupation zone. Radio

broadcasting was a public resource to be controlled by the government. To avoid

the exploitation of the media by a strong national government, as happened

during the Third Reich, the Basic Law made the state governments responsible

for radio and television broadcasting. Control of the first broadcasting

stations passed to the individual Länder governments,

although not every state has its own broadcasting corporation.

There are two public broadcasting

corporations in the Federal Republic. The first channel, ARD, was formed in

1952 as a consortium of the individual state corporations. It includes nine

regional stations in the West, and since 1992 a regional network based in the new

Länder. The second channel, ZDF, is organized as a

single corporation, rather than the consortium arrangement of ARD. All state

corporations also broadcast their own regional programming on a third channel.

|

Deutsche Welle Deutsche Welle is Germany’s international broadcaster. It produces programs for television, radio and the web–in German, English and other languages. It serves as Germany’s voice to the world, similar the Britain’s BBC and the United States’ Voice of America. DW has been broadcasting since 1953 as a public agency. |

Most of the state broadcasting

corporations follow the same organizational principles. A broadcasting

council (Rundfunkrat) sets the general

policy for the corporation and watches over the public interest. In most Länder the broadcasting council consists of representatives

of the Land government, the churches, unions and business organizations,

educational institutions, and other "socially relevant" groups. The

broadcasting council selects the members of a smaller administrative council

that supervises the actual operation of the corporation.

Public control over radio and television has

both positive and negative consequences. On the one hand, stations typically

devoted a higher proportion of their programming to public service activities

and cultural events because they are non-profit organizations. During election

periods, the political parties receive a modest amount of free advertising as a

public service (there is no paid political advertising), and extensive airtime

is made available for interviews with party representatives and debates among

party leaders. On the other hand, the quality and variety of programs reflected

its limited funding base and the small number of channels. In the past, one

might see a documentary on truck assembly plants featured during prime time viewing

hours, and the quality of many third channel programs often falls below the

standards of U.S. or British television. Critics also complained about the

broadcasters' paternalistic attitude toward the public, showing what they think

people should watch rather than what the public prefers. More problematic are

questions about the possible bias of government-controlled media. There were

also concerns that the government could use its control of the media to distort

the content of reporting, although such instances have been rare in the Federal

Republic.

Beginning with this public broadcasting base,

technological advances have changed the television environment over the past

few decades. The advent of satellite and cable broadcasting eventually ended

the government's television monopoly. Instead of three networks, most German

households now have access to dozens or hundreds of channels. Technological

progress means that one can eavesdrop on the national television of nearby

states, commercial channels, and a wide range of content. A variety of

pan-European channels have also developed.

The advent of private television does not

mean that the government is willing to relinquish its role in radio and

television. The ARD and ZDF still compete for viewers, and often they are seen

as the preferred information sources for news about politics. Although their

format and content have changed in reaction to competition with the commercial

channels, many of their key features remain. For instance, the nightly news on

both networks remain as mainstays in providing political information, and the

network’s content still reflects a stronger emphasis on education and not just

commercial programming. Despite doubts when commercial media first became

available, it is now clear that Germans have a much richer source of

information available because of these changes. A survey during the 2013

election found that 71 percent of the public claimed that television was their

most important information source on the campaign.(23)

Although television primarily serves as a

source of information on current events, the electronic media have also played

an important role in shaping political attitudes during Germany's two

democratic transitions. During the early postwar years, the FRG used its

control of the mass media to mold public images of the new political system and

develop public support for the democratic process. It was one of the few tools

of public education available to the government, enabling the new democratic

leaders to communicate directly with the citizenry. Research demonstrated a

strong relationship between media usage and political involvement.

Television also played an important role in

the process of German unification and the reshaping of the East German

political culture during the 1980s. Even before unification, West German

television could be seen in about two-thirds of the East. Moreover, when one

traveled through East Germany it was obvious that the TV antennae were pointed

toward the Western stations. Exposure to the Western media showed Easterners

another way of life and another version of history that contradicted the claims

of the East German regime. Life did not look so brutish in the West; the

freedoms of Westerners brought home the restrictions of the SED-state, and

Western living standards illustrated the lagging development of the GDR's

socialist miracle. Western news also reported on political reforms in the

Soviet Union and changes in the rest of Eastern Europe that went unreported in the

official East German press. Through the electronic media, both Germanies were already unified before the Berlin wall fell.

Online Information

While the traditional media sources are still

the dominant sources of political information, the Internet is becoming

increasingly important. People are more and more likely to turn to online news

reporting online versions of the traditional media. Nearly all of the major

newspapers now have an online presence, for example. Between 2006 and 2010

online newspaper readership doubled. In addition, Germans are avid users of

social newtworking sites such as Facebook and Wer-kennt-wen, where information

can flow between friends. Blogging (digitale

Netztagebücher) is also popular among German

youth, just as business websites such as Xing are popular among older Germans.

As of 2014, Germany had one of the highest usage rates of social media in all

of Europe. And when it is election time, voters can turn to a variety of

websites for independent information about the political parties and their

policy positions. Compared to other information sources, the Internet offers

greater variety and greater volume of information--often at the direction and

control of the individual.

The growth of online information also has a distinct

generational component, like most other features of internet usage. For

example, a recent survey found that three-quarters of teenagers visit forums,

newsgroups or chatrooms every week, a much higher precentage than among older citizens. Similarly, only about

7 percent of the overall public mentioned the internet as their most important

source of information during the 2013 elections.(24)

However, the Internet was the most important information source to only 2

percent of people aged 70-79, compared to 28 percent among those under age 30.

Among the under 30 age group, the Internet was only second to television as an

information source. (Newpaper usage runs in the

opposite direction, from only 5 percent citing it as most important among the

under 30 group, to 20 percent among people aged 70-79). Thus the overall

patterns of information should continue to change in the decades ahead.

The growth of online information also has a distinct

generational component, like most other features of internet usage. For

example, a recent survey found that three-quarters of teenagers visit forums,

newsgroups or chatrooms every week, a much higher precentage than among older citizens. Similarly, only about

7 percent of the overall public mentioned the internet as their most important

source of information during the 2013 elections.(24)

However, the Internet was the most important information source to only 2

percent of people aged 70-79, compared to 28 percent among those under age 30.

Among the under 30 age group, the Internet was only second to television as an

information source. (Newpaper usage runs in the

opposite direction, from only 5 percent citing it as most important among the

under 30 group, to 20 percent among people aged 70-79). Thus the overall

patterns of information should continue to change in the decades ahead.

In summary, all these various media outlets

are important sources of information about political events. Because these

media are treated as public resources, an usually

large share of the programs are devoted to news, political discussions, current

affairs, and other information programs. The public information content of

German television ranks among the highest in Western Europe. Westerners thus

rely on television as a primary source of information, and viewership is even

higher in the East. When surveys ask about the most common sources of information,

television is cited as the most common source of political information: 96

percent say they use television as an information source; newspapers, friends

and colleagues, 87 percent;85 percent; magazines 51 percent; and internet 48

percent.(25) Use of these multiple sources makes for an

informed and aware public.

Conclusion

The past two decades produced important

changes in how the German public learns about politics and how political

leaders communicate with the citizens. Most important, the new citizens in the

East have been integrated into the information network of the Federal Republic.

They moved from a closed system where the GDR government controlled access to

information to an environment where there is a near over-abundance of

information to digest. In addition, the information context has changed in West

and East as a function of technological change, ranging from the spread of

satellite and cable television to the explosive growth of the internet. Today

the average citizen has access to a wider and richer array of information about

politics and society. If the old German saying “Wissen

ist Macht” (knowledge is

power) is correct, then the contemporary democratic citizenry should be very

powerful.

Sterling Fishman and Lothar

Martin, Estranged Twins: Education and Society in the Two Germanys

(New York: Praeger, 1986).

Peter Humphreys, Media and Media Policy

in Germany: the Press and Broadcasting since 1945. New York and Oxford:

Berg Publishers, 1994.

John Rodden, Repainting

the Little Red Schoolhouse: A History of Eastern German Education, 1945-1995.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Meredith Watts, et al. Contemporary

German Youth and Their Elders (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989).

Notes

1. Gabriel Almond and G. Bingham Powell, Comparative

Politics (Boston: Little, Brown, 1978), chap. 4; David Easton and Jack

Dennis, The Development of Political

Attitudes in Children (New York: McGraw Hill, 1969).

2. Ralf Dahrendorf, Society

and Democracy in Germany (New York: Doubleday, 1967), p. 139.

3. Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba,

The Civic Culture (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1963), chap. 12.

4. Also see chapter 4; David Conradt,

"Changing German Political Culture," in Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba, eds. The Civic Culture

Revisited (Boston: Little, Brown, 1980); Kendall Baker, Russell Dalton and

Kai Hildebrandt, Germany Transformed (Cambridge: Harvard University

Press, 1981).

5. From author’s analysis of the 1999 World Values Survey

in Germany (www.worldvaluessurvey.org);. The percentage of each age

group who say parents should stress independence in raising their children:

|

|

18-24 |

25-34 |

35-44 |

45-54 |

55-64 |

65+ |

|

West |

84 |

83 |

79 |

73 |

67 |

56 |

|

East |

86 |

73 |

68 |

75 |

63 |

57 |

6. Hans Oswald, "Political Socialization in the New

States of Germany." In Miranda Yates and James Jouniss

eds., Roots of Civic Identity: International Perspectives on Community

Service and Activism in Youth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

2006; Christiane Lemke, "Political Socialization and the 'Micromilieu'" in Marilyn Rueschemeyer

and Christiane Lemke, eds. The

Quality of Life in the German Democratic Republic (New York: M.E. Sharpe,

1989).

7. Deutsches

Jugendinstitut, Deutsche Schüler

im Sommer 1990

(Munich: Deutsches\ Jugendinstitut,

1990).

8. See endnote 5.

9. Meredith Watts, et al. Contemporary German Youth

and Their Elders (New York: Greenwood Press, 1989); Dalton, Citizen

Politics, 6th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2013), chap. 5.

10.Brian M. Puaca, Learning Democracy: Education Reform in West

Germany, 1945-1965. Oxford: Berghahn Books,

2009.

11. Judith Torney, A. Oppenheim,

and R. Farnen, Civic Education in Ten Countries,

International Studies in Evaluation, vol. 6. (Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell, 1975).

12. Sterling Fishman and Lothar

Martin, Estranged Twins: Education and Society in the Two Germanys

(New York: Praeger, 1986).

13. Friedrich Walter and Hartmut

Griese, Jungend

und Jugendforschung in der DDR (Opladen: Leske and Budrich, 199_).

14. Rosalind Pritchard, Reconstructing Education: East

German Schools and Universities after Unification (New York: Berghahn Books, 1999).

15. Max Planck Institute, Between Elite and Mass

Education (Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1982).

16. Another distinctive feature of the Eastern educational

system was the extensive network of state-supported day care and kindergarten

facilities that enabled women to work. More than 90 percent of all 3-6

years-olds were in kindergarten; see John Rodden, Repainting

the Little Red Schoolhouse: A History of Eastern German Education, 1945-1995.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

17. John Rodden, Repainting

the Little Red Schoolhouse: A History of Eastern German Education, 1945-1995.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002; Krisch, The German Democratic Republic, pp.

153-158.

18. Meredith Watts, et al., Contemporary German Youth

and their Elders (New York: Greenwood, 1989), ch.

3.

19. Almond and Verba, The

Civic Culture, pp. 88089; Holli A. Semetko and Klaus Schoenbach,

"The Campaign in the Media," in Russell Dalton, ed. Germany Votes

1990(Oxford: Berg, 1992).

20. Karl Christian Führer and Corey Ross eds., Mass

Media, Culture and Society in Twentieth-Century Germany.. London: Palgrave Macmillan: Berg

Publishers, 2006.

21. German Longitudinal Election Study, 2013 Election

Survey (http://gles.eu/wordpress/english/).

22. Führer and Ross eds., Mass Media, Culture and

Society in Twentieth-Century Germany.

23. German Longitudinal Election Study, 2013 Election

Survey (http://gles.eu/wordpress/english/).

24. German Longitudinal Election Study, 2013 Election

Survey (http://gles.eu/wordpress/english/).

25. Dalton, Citizen Politics, pg. 23.

copyright 2014

Russell J. Dalton

University of California, Irvine

rdalton@uci.edu

Revised July 3, 2014