| |

Tandas

and Cundinas:

Mexican-American and Latino-American Rotating Credit Associations in Southern

California

Rosalba Gama, Delma Medrano and Luis Medrano

Origins

and Background

The monetary practice we chose to focus on for our project is the tanda.

The tanda is a form of rotating credit association and a monetary practice

that we, as Chicanos, have grown up knowing but never really understood

the details, except that our parents or other relatives participated in

them. That is why we have chosen to research the tanda, which is rooted

deeply in the Mexican and Latin American culture and has evolved into

a common practice within Mexican-American and Latino-American enclaves

in southern California.

The term “rotating credit associations” refers to "an

association formed upon a core of participants who agree to make regular

contributions to a fund which is given in whole or in part to each contributor

in rotation" (Cope and Kurtz 213). The basic definition given here

explains the foundation for the manner in which a tanda functions, but

specifically for the tanda. What is left out of this definition is the

fact that in a tanda the association is built mostly on trust. "Without

a willingness to engage in generalized reciprocal relations based on mutual

trust, the associations could not function" (Velez-Ibañez

7). Confianza, or trust, is the key aspect of the tanda and is what allows

this type of credit association to exists within the community. How did

this type of association begin? Where did the tanda come from? How is

it that a group of people, sometimes strangers, contribute their hard

earned money to a pot in which they and the other participants expect

to receive the tanda amount on their given date?

Rotating credit associations exist in various parts of the world. Let's

recall that rotating credit association is the general term used to the

type of association that can be formed by any given peoples. The specific

ways in which these rotating credit associations function and who participates

in them vary from culture to culture. Because rotating credit associations

are a form of reciprocity or gift giving among peoples, similar practices

can be traced back hundreds of years among numerous cultures around the

world. The tanda, a form of rotating credit association, originated in

Mexico and is known among the Mexican American and Latino American community

of southern California and various other parts of southwestern United

States.

Practices involving rotating credit associations including the tanda are

known to have originated from people who lived in agrarian societies.

These people then shifted from a traditional agrarian society to a commercial

one and in this transition formed credit associations, influenced by the

dominant commercial society (Velez-Ibañez 7). This suggests that

the tanda is formed solely for economic purposes. The tanda usually involves

people who are interested in developing a money saving system and more

importantly in building relationships with the organizers of the tanda

and all other participants. In Mexico, the origins of the tanda and similar

practices involve the need for the people of the working class, and in

some cases the middle class, to rotate scarce resources among themselves,

in this case money. In the United States, specifically southern California,

the tanda was introduced through migration from the working class of Mexico

to the United States. This practice has survived in the United States

because the immigrants that migrated from Mexico to the United States

continued to be of the working class and being immigrants, relied on the

tanda as a form of money saving.

The origins of the tanda in Mexico are said to have begun in and around

Puebla, Mexico. The manner in which the practice of credit associations

arrived in Mexico is postulated to have come from the Chinese. Velez-Ibañez

states that, "when Chinese contract workers established residence

in Mexico after 1899, they brought with them a Chinese version of rotating

credit association known as the hui" (16). Chinese labor was known

to have been distributed in many areas of Mexico and their practice could

have made some contribution to the emergence of the tanda years later.

Tanda is the name that has become dominant among the people who participate

in it in Mexico and those in the United States. The word tanda literally

means turn or alternative order. However, there are various other names

that have been given to this practice of rotating credit association.

Another name that is widely used, probably second to tanda, is cundina.

In Spanish “cundir” means to spread. Other names that have

been used according to area include: quiniela in Chihuahua, mutualista

in Yucatan, vaca in Texas, and bolita in Veracruz. Interestingly enough,

prisoners from the Leucunberry prison, a prison in Mexico, have created

their own form of rotating credit association. They have coined it cannabis

mexicana vacas, which was a cooperative savings group organized to buy

larger amounts of marijuana for a discount. Unlike the Tanda, this was

not made up of individual equal shares, and because of this, the amount

of marijuana given was equal to the amount of money contributed (Velez-Ibañez

22).

Other interesting names that have been used are tanda de cuates, cuates

meaning pals, and coperacha, or cooperative. In the tanda de cuates, about

five people are involved whose specific goal is to purchase alcoholic

beverages, from which results an unintended consequence prestige for the

person who can consume the most alcohol without becoming intoxicated (Velez-Ibañez

23). The coperacha is a more general than the tanda de cuates because

the money contributions are used for things like family dinners or for

financial assistance to a friend in need. What remains certain is that

all of these names are only variants of the most dominant term, the tanda,

which is what has persisted in the United States.

The

Process: How it Works Today

In our search to get the most up-to-date and accurate information about

tandas we interviewed four people who have participated in these tandas

for a minimum of four years. Participants A, B, and C are female immigrants

from Mexico and Participant D is an immigrant from El Salvador. All four

women live in Santa Ana, California. Our interview questions revolved

around their interest in participating, their experience, the organization

and procedure, possible risks, and their role within the tanda. The women’s

interests and perception of possible risks are similar, but there were

a variety of organizational concepts that correlated with the woman’s

status within the tanda.

Participant

A

Participant A, a Mexican immigrant now living in southern California defines

the terms “tanda” and “cundina,” which she uses

interchangeably, as a community composed of people you know and trust.

She began participating at the age of 15 and has been a constant participant

in tandas for the last 16 years. Participant A considers the tanda to

be a very effective way to save money and control needless expenditures.

She also claims that she is so used to participating and following the

tanda routine that she does not want to stop. Although this may resemble

an addiction, Participant A perceives the continuous participation in

tandas positively because it serves as an incentive to save money for

paying off debts, traveling, and/or preparing for big parties or ceremonies

such as quinceañeras and weddings.

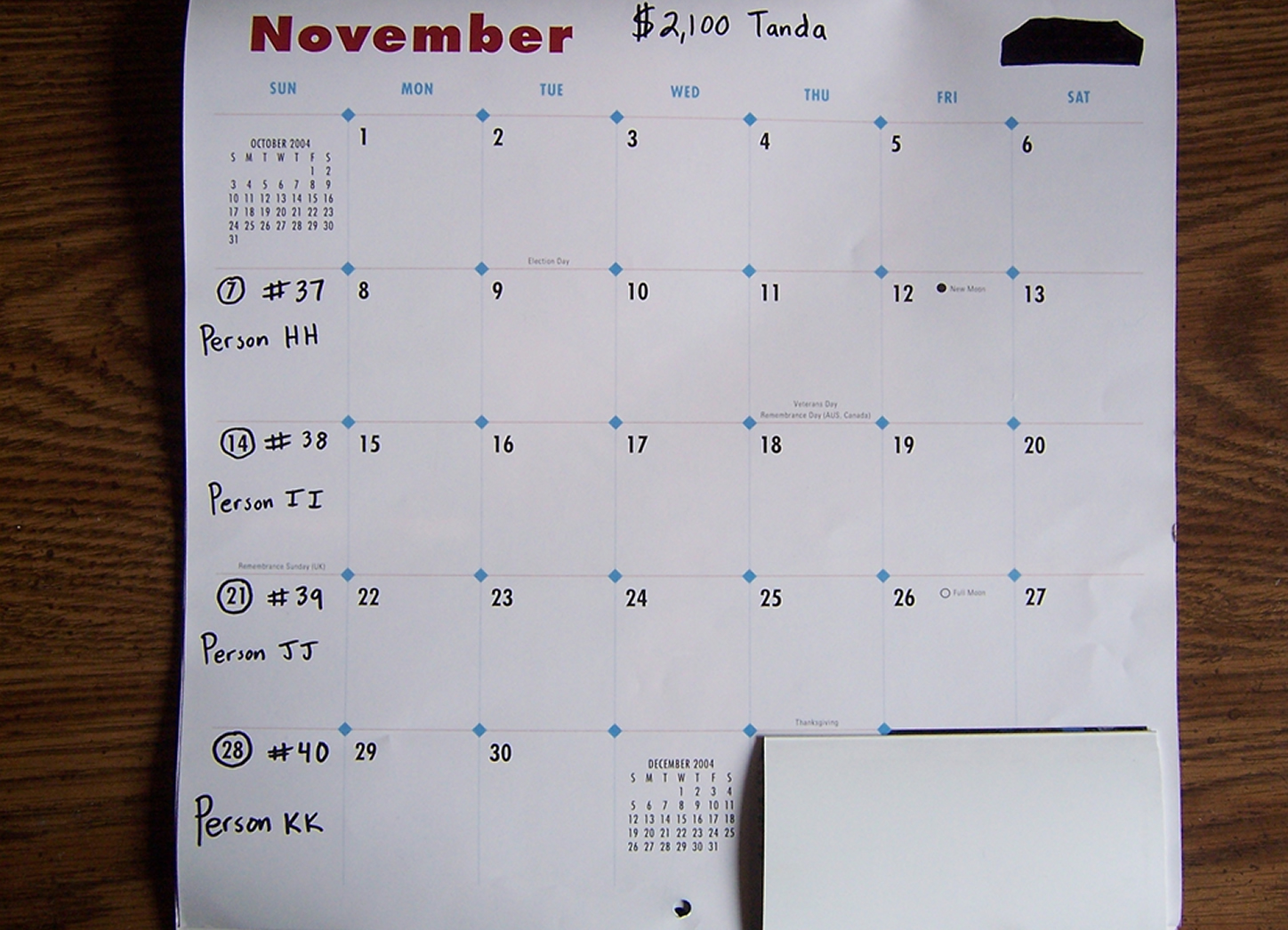

The amount of credit that rotates within the tanda can vary in amount.

The total contributions of the tanda she participated in 16 years ago

participants summed up to $200. This means that every week x number of

people would all pitch in a pre-determined amount of money to compile

$200 each week. Every week a different person would get the $200. Currently

she was participating in a tanda that would amount to $2,000 every week.

There were ten participants in this tanda, and every week they would pitch

in $200. One of the ten different participants would receive the $2,000

each week, for ten weeks. Speaking specifically about her community’s

tanda, she stated that seniority determined the weekly order of who received

the tanda amount, as opposed to random selection. The names of the people

that had been selected were then written on a weekly time sheet, and were

crossed off as each person received their tanda amount. It was also common

in their tanda for people to participate twice. However, this meant that

their contribution would be doubled. For example that participant in the

tanda would receive $4,000, by the end of the entire process, but would

also have had to contribute $400 every week.

Because of her long experience Participant A was currently an organizer

of the tanda. This means that she participates within the tanda, but is

in charge of deciding the sequence of payments according to seniority,

keeping the weekly time sheet and keeping track of who gets paid when,

making sure everybody makes their payments on time every week, collecting

and distributing the money. She mentioned that her position as the organizer

could sometimes be problematic when a friend she knows to be irresponsible

wants to join. While the decision to not let this friend participate in

the tanda may sour the friendship, it gains the organizer respect and

trust from the other participants.

Because of her strict regulation of the participants, there had not been

anyone who had defaulted, but if that were the case, as organizer, she

would have to take over the payments. In some instances when people had

paid their contributions late, she collected a late fee of $20 for the

inconvenience but also to set an example. In fact she mentioned it was

not uncommon for participants who did not have for the weekly payments,

to borrow from other participants in order to make payments and prevent

the tanda from falling apart. It was up to their discretion to repay each

other in timely fashion after getting paid from work or receiving their

share of the tanda.

Participant B

Participant B, an immigrant from Jalisco, Mexico, also living in Santa

Ana, California has had 15 years of experience as a constant participant

in tandas. She has participated in at least one tanda per calendar year

since her migration to the United States. When asked why she participates

in tandas, Participant B echoed the response of Participant A, stating

that the tanda is a great way to save money, but also mentioned that it

is helpful in making big purchases when funds aren’t available.

She alluded to her ability to purchase a vehicle through the use of tandas.

She also explained that during the time that she wanted to purchase her

vehicle all of the other tanda participants were also interested in making

big purchases. In order to accommodate all of their needs, they organized

three tandas that year in which each person contributed $200.00 per week

for a total of 27 weeks (each tanda was 9 weeks long).

When asked about not choosing to save her money in a bank, but rather

within a rotating credit association, Participant B expressed her perception

of the bank as an institution that was waiting for any opportunity to

charge a fee for “safe keeping,” something that was not a

concern within the tanda. She explained that she preferred tandas because

the group had a better, more tangible control of the money and a personal

understanding of each other’s needs. The group of people she participates

in is constituted by her sisters, which, together, make up the total of

nine contributors to the tanda.

This particular family tanda is very exclusive and is only organized for

the use of the sisters. The sisters alternate to be organizers every time

a new tanda is proposed. To keep track of the contributions, an agenda-like

book is passed from organizer to organizer every time a new tanda is initiated.

Touching on the subject of fraud, Participant B shared that since the

participants in her group are all sisters, they have a moral responsibility

to follow through with the tanda. They cannot flake out because they are

bound by the same goal, to help each other out.

Participant

C

Our third interviewee, also from the state of Jalisco, Mexico, is currently

living in southern California and is an employee at a local factory in

Santa Ana, CA. She has participated in 5 tandas in the last four years,

since she was introduced to tandas in the workplace. Her reasons for participating

in the tanda include financial necessity but also the enduring hope that

she will increase the amount of money in her savings account. Up until

today though, she has been unable to accomplish that goal since she often

finds herself using the tanda money to pay the mortgage and other bills.

She mentioned that sometimes she has been able to increase her savings,

but then sometimes finds herself having to withdraw money from her account

to make payments on the tanda.

Participant C does prefer the tanda over banking institutions because

it allows her to count on the set tanda amount of money and not worry

about taxes or fees. However she believes that tandas aren’t that

effective because of the constant pressure to make the weekly payments.

She stated, “you’re always worrying about forgetting to pay

each week. Besides if we had that money in our account, we might be able

to gain more, like in interest or something, but we don’t leave

it there, in hopes that we will be able to save up a little money or hacerlo

rendir (make it last).”

The tanda in her workplace was particularly large. The tanda was made

up of 20-30 participants, including both gender. The tanda participants

were determined by the Lead, the person who delegates the daily tasks

to the workers and reports to the supervisor. The Lead opens participation

to whoever wants to participate, and from there selects those who have

more time working in the factory and have permanent working status. Participant

C also mentioned the use of personal knowledge of who will not cheat or

take off with the money. Once chosen, each participant contributes $50

each week, for a pre-determined set of weeks. Participant C’s pointed

out that it was beneficial to have more participants because the tanda

amount collected by each participant would be larger.

The order in which the tanda amount is collected every week is randomly

selected through drawing numbers out of a hat. As was the case with Participant

A, in this tanda community people are allowed to participate more than

once by drawing out more than one number. For example, if one person draws

3 numbers, she will be responsible for contributing $150 every week. The

Lead, as organizer is responsible for collecting and distributing the

money. She waits for everyone to hand in the money before distributing

it. Despite the size of this tanda community, there is no history of fraud.

Participant C attributes this to the fact that, “its is all people

we know, people that are trustworthy,” but also the fact that there

is no way of escaping the community in case of fraud, other than deliberately

losing employment. She mentioned that sometimes people don’t turn

their money in on time because, “ they are night shift workers and

they hand in their money the next day, or sometimes people turn in personal

checks instead of cash.”

Participant C stated that solidarity was difficult to attain in this tanda

community because people weren’t punctual in turning in their money

and some got resentful. It was in the case that somebody knew they were

going to miss work, when they called co-workers to ask for them to turn

her money in, that relationships were reinforced. In Participant C’s

case expressed that she would not let herself miss a week by paying in

advance if she knew she was gong to be absent.

Participant D

Our fourth interviewee, Participant D, is from El Salvador and is also

residing in Santa Ana, California. Her case is somewhat different from

the three mentioned above. The primary reason for why she started participating

in the tanda ten years ago is because she was in desperate need of cash

and she knew a friend who was in charge of a tanda. Today Participant

D uses the tanda not only to get her bills and rent paid but also to invest

in her small business at the swap meet. After getting to know everyone

in the tanda community, she decided that she wanted to be the organizer

and gathered a group of people who she knew she could trust, like her

brothers, sisters and long-time co-workers. Now she participates in tandas

year round.

As the organizer, she gets to make her own rules. She usually gets two

places within the tanda roll sheet, the first and the last week. She does

this in case profits from her business are not substantial, in order to

take home some money at the end of the tanda. This particular participant

will only do tandas that last eleven weeks because she says it doesn’t

make sense to make it for less. For example, “when only ten memberships

(participants) contribute into a $1,000.00 tanda, the total amount of

the fund that is rotated among the members in any given week is the sum

of the contribution from all memberships including the recipient for that

week. However, only $900.00 actually changes hands; the $1,000.00 includes

the $100.00 from the recipient. When the eleven memberships exist, the

total fund is met by the ten non-recipients (Kurtz and Showman, 68).”

When asked about the risks of this type of rotating credit association,

she said that for the most part people who participate do it because they

want to save money and leave their tanda savings for an emergency. There

have been occasions when she has misjudged a person’s character

and has been left with paying other members part of the contribution as

well as her own for the sake of keeping the tanda intact. She says that

these are risks her community is willing to take but that it is also cautious

of who is invited to participate.

When Participant D first joined the tandas, she was confidentially acting

as her friend within the organization. As was agreed, Participant D received

her friend’s share as long as she made payments every week, in the

place of her friend. Participant D’s friend took a significant risk,

the essence of the tanda, because Participant D had received the first

number. Had Participant D been shady, she could have taken off with the

money without making any payments, but the initial payment. Participant

D followed through with every payment as a result has since been seen

as someone trustworthy and responsible enough to partake in the tanda

community. In this way the tanda grows in participants and makes the participation

of all the members even more so appealing.

Tandas

and Cundinas in anthropological perspective

The political and social position of Mexican Americans in the United States

is essential in the study of Tandas and Cundinas in southern California

primarily because of immigrant status and lack of social capital. Evident

in the interviews, Tandas and cundinas tend to emerge from social support

systems, more specifically ethnic support systems. This could be understood

as an effort by members of minority groups to become integrated into the

economy without having to deal with bank or government officials or as

resistance to bank institutions.

In learning about tandas and cundinas, two theories must be considered,

embeddedness theory and enclave-economy theory. Embeddedness theory states

that, “‘structures of social relations’ always influence

economic behavior, to the extent that overlooking their influence is a

grave error even when treating differentiated institutions in advanced

societies.” (Butler and Kozmetsky, 174) This theory obliges the

researcher to understand why it is that tandas are organized most often

in the workplace, and as mentioned above, by various ethnic groups. In

analyzing the social relations that influence economic behavior, the researcher

must understand the political and social context of the workplace and

why they lead to the formation of tandas and cundinas.

Mexican Americans have a long history of marginalization in the workplace.

Since the late 1800’s, American businesses, opportunistically, have

been bringing thousands of uprooted farmers, peasants, and other laborers

to the United States. The prosperity of these businesses has depended

on low wage, flexible labor. In order to preserve this type of labor,

employers recognize the advantage of keeping workers in need, in fear

of losing their jobs. To ensure necessity and fear within workers, employers

limit benefits, guarantees, progress, and do not allow the laborer to

decide the type of work she will engage in. The treatment of Mexican Americans

in the workplace is reflective of their treatment within educational and

court systems in the United States. The educational and court systems

contribute to the cheap labor pool vital to American businesses through

the mistreatment, tracking into vocational studies and criminalization

of Mexican American youth.

This treatment and marginalization of Mexican Americans within the workplace

and the nation is a primary factor in the creation of tandas. In order

for Mexican Americans to survive and succeed within a society that seeks

to oppress and exploit them, they must develop social support systems.

In her book, The Unmaking of Soviet Life, Caroline Humphrey gives an ideal

example of a social support system providing economic aid. Humphrey states

that “over 30 percent of the population of Russia has an income

below the ‘threshold of survival,’ that is, they must use

existing stocks, sales of property, or loans from kin and friends to stay

alive,” (Humphrey, 41). Because of social connections and relations,

Russians have been able to participate and survive in the national economy.

This underlines the importance of social relations in the participation

of Mexican Americans within the US economy.

This position of dispossession and marginalization of particular ethnic

groups encourages the formation of ethnic enclave support groups, like

the tanda. In Immigrant and Minority Entrepreneurship, Min Zhou speaks

of ethnic enclave support groups, as those bound by a, “common nationhood,

familiar cultural environment, and densely knit networks,” and defines

the enclave itself as, “an integrated cultural entity maintained

by bounded solidarity and enforceable trust- a form of social capital

necessary for ethnic entrepreneurship,” (Butler and Kozmetsky, 41).

These groups form out of necessity, to encourage assistance amongst members

who share the lack of opportunity within the larger economic system. Through

these groups, members share experiences, knowledge and support regarding

the system that denies them based on what seems to be ethnicity.

The role of Mexican Americans in the US economy is that of a people who

are dispossessed, especially those who have recently entered the country

and have not yet obtained documents. Although they contribute significantly

to the US economy, they are not recognized and therefore cannot participate

in a variety of public institutions and cannot reap benefits generally

available to citizens. Humphrey discusses the importance of status and

documentation, in regards to people who are accepted and embraced by larger

society and those who are dispossessed. She defines the dispossessed people

in Russia as, “people who have no connections or support from the

system,” and it is because of this lack of connections that, “they

do not want to participate in the bureaucracy or institutions within the

dominant system,” (Humphrey, 31). And part of the reason because

they do not want to participate is because they lack the documentation

to do so. Documents in Russia, like in the United States, confirm identity

and validate contributions to the nation.

Without documents an immigrant cannot seek employment legitimately, open

a bank account, or collect income tax. “The dispossessed, we can

now see, come in many categories, signaled by deprivation of one or another

document; but what is important is that a loss of one official status

threatens the unraveling of the whole edifice, that is the descent into

the wilderness of having no entitlements at all,” (Humphrey, 26).

This is parallel to the situation of Mexican Americans in southern California.

Without one document (i.e. green card) the immigrant cannot obtain any

other. For example, she cannot obtain a social security card without proof

of residence, which will then prevent the possibility of applying for

employment or a bank account. Reasons why Mexican Americans do not have

equal access to economic and employment opportunities as a result of lack

of documentation, include, “lack of credit ratings, collateral,

or are the victims of ethno-racial discrimination,” (Butler and

Kozmetsky, 171). Whereas Mexican Americans do not have equal access to

economic or employment opportunities, they feel compelled to abandon the

larger banking institutions and develop their own support groups within

their ethnic enclave.

Works Cited

Butler, John Sibley and George Kozmetsky, ed. Immigrant and Minority Entrepreneurship:

The Contunious Rebirth of American Communities. Praeger. Westport: 2004.

Cope, Thomas.

Default and the Tanda: A Model Regarding Recruitment For Rotating Credit

Associations. Ethnology, 19:2 (1980:Apr.)

Humphrey,

Caroline. The Unmaking of Soviet Life: Everyday Economies After Socialism.

Conrell University. Ithaca: 2002.

Kurtz, Donald

V. The Tanda: A Rotating Credit Association in Mexico. Ethnology, 17:1

(1978:Jan.)

Velez-Ibanez,

Carlos G. Bonds of Mutual Trust: The Culture System of Rotating Credit

Associations Among Urban Mexicans and Chicanos. Rutgers University Press.

New Brunswick: 1983.

|

|